The god Dionysus is currently almost automatically associated with wine, drunkenness, and madness. However, in its origin, he was a deity associated with the rebirth of life, enthusiasm, and mysteries. His origin is uncertain because, although the Greeks themselves consider him a foreign god, arriving from some place in Asia Minor (Anatolia or Libya), various pieces of evidence link him to Hellenic culture since the Mycenaean era when he is mentioned on tablets as “DI-WO-NI-SO-JO,” and even his origin can be traced back to Minoan Crete. However, Dionysus appears as a civilizing and traveling god, traversing the known world to the Greeks, from distant India, Egypt, and Asia Minor to the Hellenic peninsula, teaching men agriculture, grape cultivation, and its drink, wine, and establishing mysterious rituals.

Myths of Dionysus

The name of Dionysus has an uncertain origin; it is often translated as the “Zeus of Nysa” (the genitive of Zeus is “Díos”), with Nysa being either a nymph who raised him as a child or the mountain where he spent his childhood. There are several myths about his birth, all having in common his semi-divine origin as the son of Zeus and a mortal woman, Semele, and his condition of being “born twice.”

According to one of these myths, Semele, instigated by Hera, asks Zeus to appear to her in all his power. However, she cannot bear the sight of the god and dies. Zeus then takes Dionysus from Semele’s womb and places him in his thigh to complete his gestation, from which he will ultimately be born.

According to another myth, Hera, after distracting Dionysus as a child with toys, sends the Titans against him. They tear him apart, and the goddess Rhea, Zeus’s mother, finds the pieces and revives him by boiling them in a cauldron. Here, elements related to Orphic mysteries appear, reminiscent of Egyptian mythology, with the resurrection of a dismembered god (like Osiris) and even the symbol of the cauldron, resembling the magical cauldron of the Celts, through which a journey to the underworld and subsequent rebirth was accomplished. This relationship also appears in myths of Dionysus’s journey to Hades to reclaim his mother Semele.

We can see, therefore, the connection of Dionysus with the rebirth of life after death. The common elements that the Christian Mass ceremony shares with the cult of Dionysus and Osiris are very evident, where one relates rebirth with wine, and the other represented dismemberment with the distribution of sacred bread. The mysteries of Dionysus, attributed to Orpheus, were intended to induce participants to unite with the god through enthusiasmós, a word derived from “en-théos” (god within). Over time, however, the rites (orgiai or bacchanals) declined and degenerated, distorting his image to this day as unrestrained feasts leading to drunkenness and group sex.

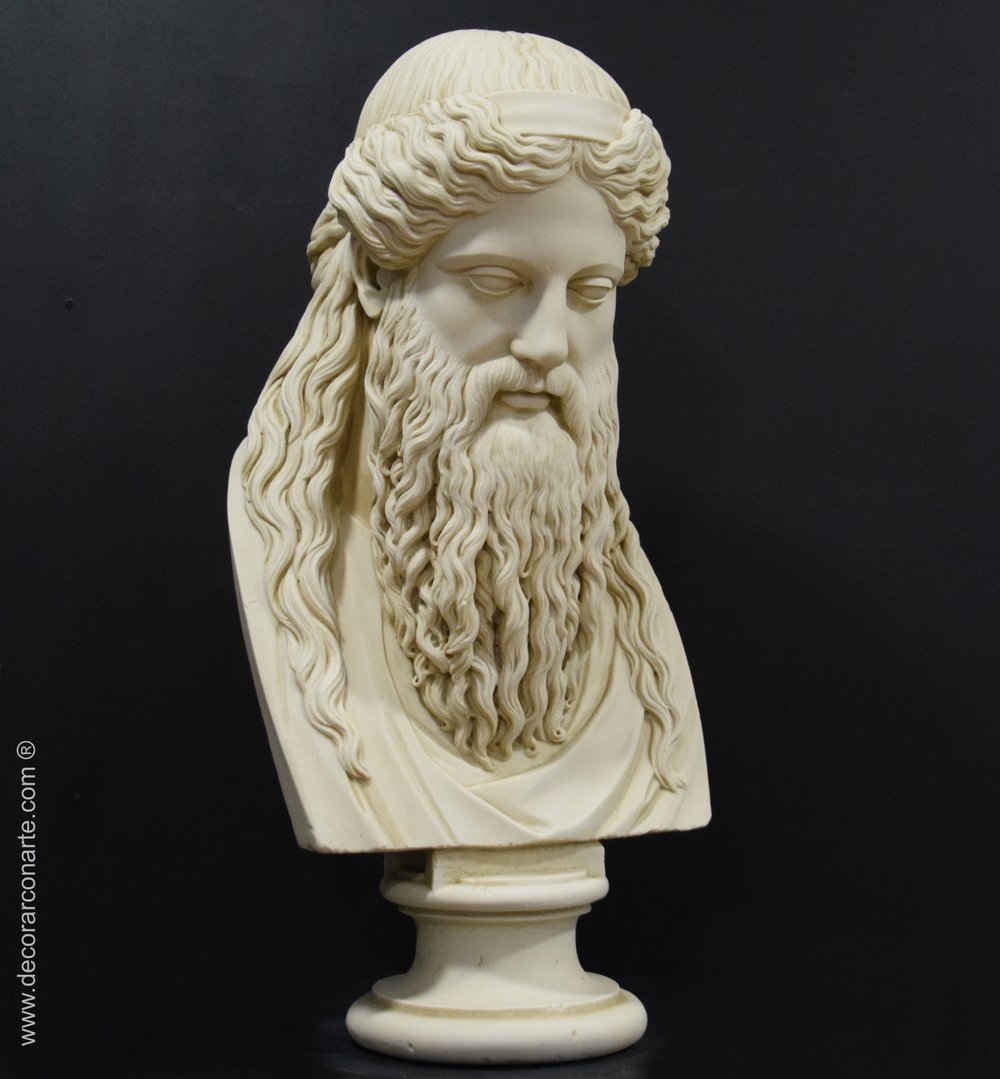

The same distortion occurred with the figure of Dionysus himself, who came to be represented as a bearded god in mature age, dressed in leopard skins (similar to those worn by Egyptian priests), to the images that have survived to this day of a beardless young man with signs of drunkenness.

Dionysus in Archaic Art

As we have mentioned above, the image of Dionysus has changed significantly, following the same process of “rejuvenation” that other gods experienced, such as Hermes..

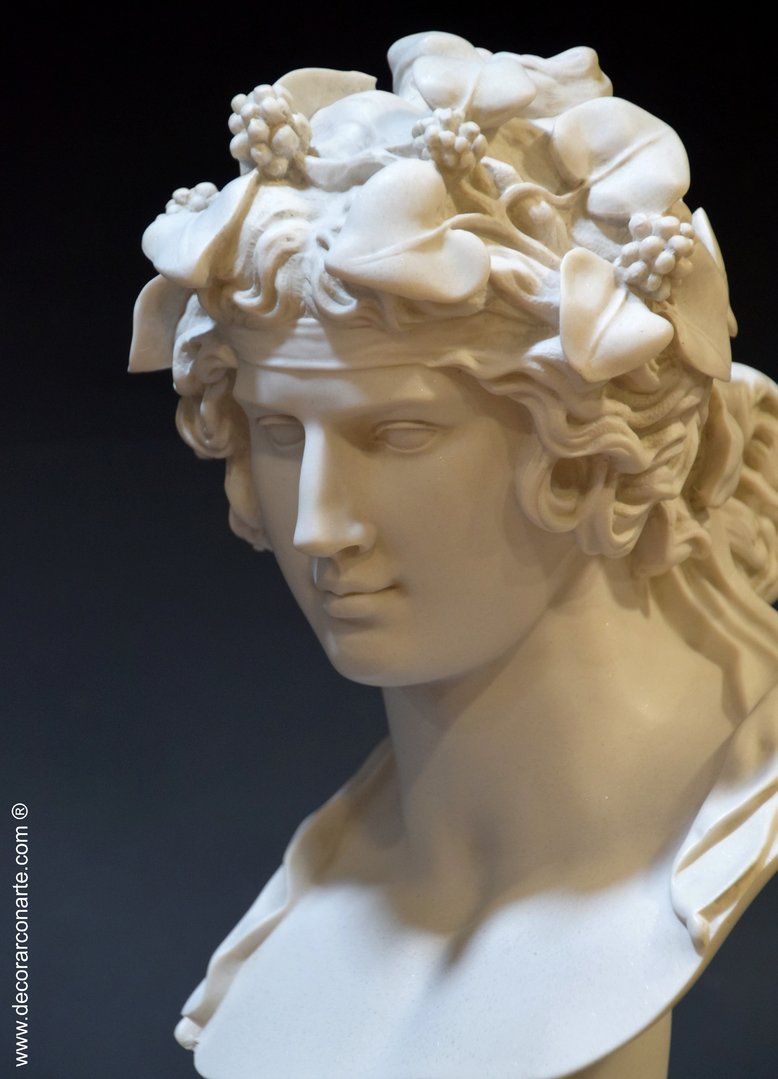

The attributes associated with Dionysus were a crown of grape leaves, sometimes accompanied by bunches of grapes, the thyrsus, a staff entwined with ivy and crowned with a pinecone, the skin of a goat, fox, panther, or leopard as clothing, accompanied by a retinue of satyrs, centaurs, silenuses, nymphs, and bacchants or maenads. The animals associated with him were the snake, the bull, the leopard, and the panther, with these animals depicted pulling his chariot.

In the archaic period (6th century-early 5th century B.C.), he appears on pottery as a mature, bearded man with long hair, crowned with ivy. One of the most famous images is that of Dionysus reclining on a ship with a vine wrapped around the mast and dolphins. This image refers to a myth where Dionysus was kidnapped by pirates; the god made a vine grow on the ship and summoned various animals, frightening the pirates, who jumped into the sea and were transformed into dolphins.

He is also depicted alongside Silenus, his mentor, and with satyrs and centaurs, with the legs of a goat and horse, forest spirits.

Dionysus in Classical-Hellenistic and Roman Art

The metamorphosis of Dionysus occurred during the Classical and Hellenistic periods, extending into Roman art. From this period, we have the famous sculpture by Praxiteles of Hermes with the young Dionysus, where the messenger of Olympus would likely hold a cluster of grapes in his right hand that the young Dionysus would attempt to reach.

Later representations would abandon the bearded god aspect, appearing as a beardless young man with his typical attributes, with the exception of a Hellenistic-Roman statue called Dionysus-Sardanapalus, as it was erroneously attributed to an Assyrian king in the 18th century. The Romans adopted Dionysus under the name Bacchus, derived from one of his epithets, Bacchos, and associated him with the Roman god Liber, appearing as the god of drunkenness in numerous mosaics and paintings.

One of the most significant works to mention is the paintings from the so-called Villa of the Mysteries in Pompeii. In this house, very well-preserved murals were found, reflecting the initiation of a young woman into the Dionysian mysteries. In these paintings, you can observe the stages of preparation led by priestesses and the epiphanies or appearances of divinities, both from the satyrs of the Dionysian procession and Dionysus himself, who is portrayed alongside his wife Ariadne (the daughter of King Minos, whom he married after finding her on an island after being abandoned by Theseus), dominating the central part of the enclosure with his thyrsus. These are strange and evocative scenes of rituals whose main meaning eludes us, revealing both fear of the sacred and the liberation from that fear through the revelation of divinity.

Renaissance and Baroque Art

After the long and dark parenthesis of the Middle Ages, in the 15th century AD, thanks to the impetus of the Neoplatonic schools, classical Greco-Roman culture began to be rescued from oblivion. Archaeological excavations became fashionable, and the collection of ancient works inspired great Italian artists, and Greek gods and heroes returned to populate European iconography.

Nietzsche contrasted the figures of Apollo and Dionysus as the balance and serene harmony of the former against the excess and unbridled force of the latter. This comparison can help us establish a parallel with the Renaissance and the subsequent artistic movement, the Baroque. What was serenity and balance in Renaissance art will become movement, emotion, and passion in Baroque art. Perhaps this is why Dionysus is one of the favorite gods of Baroque art, associated with wine, frenzy, and drunkenness.

Among his representations, we can highlight those of three great masters of painting: Velázquez, Caravaggio, and Rubens. The painting “The Drunks or the Triumph of Bacchus” by Velázquez shows the god surrounded by common people, who, joyous and with flushed faces from alcohol, look at the viewer, making them part of their ethereal joy. In this case, as often happens with mythological works by the brilliant Sevillian painter, the god stands out from the rest of the characters, his color is paler and brighter, as if radiant, and he does not exhibit obvious signs of drunkenness.

Caravaggio, on the other hand, painted the god with these signs, a slightly reddened face and half-closed eyes. In another painting, he takes this demystifying treatment to the extreme; it is the painting of “Sick Bacchus,” where we can see the poor god, pale, with an almost greenish hue, dark circles under his eyes, and white lips, a victim of the hangover caused by the effects of wine.

Finally, Rubens’s Bacchus, the one that comes closest to caricature. True to his style, the Flemish painter portrays the god as well-fed, with a satyr behind him and a lioness at his feet.

As a culmination of all this, we could mention the film “Fantasia,” in which accompanying Beethoven’s “Pastoral,” Disney depicts Bacchus as a chubby god riding a donkey-unicorn. Perhaps this is the best summary of how the image of this complex god has remained in popular imagination, forgetting the ancient representations of the god.

In conclusion, we can point out that Dionysus is one of the gods most explored by European art, and at the same time, one of the most misunderstood and mistreated. It is challenging to understand the profound meaning he had in ancient Greece, as well as that of his mysteries, and his image has come down to us quite distorted. It is worth tracing the ancient myths and stopping at the old pottery fragments or the enigmatic images of the Villa of the Mysteries, trying to intuit the ancient sense of the sacred hidden within them.

Here you can see some of our reproductions of Dionysus sculptures in our catalog: